Many species of native wildlife are impacted both directly and indirectly by livestock.

Both elk and bighorn sheep have been observed moving away from cattle. Livestock will physically displace elk and bighorn sheep and cause them to move off an area of forage or a water resource.

Cattle across the West require thousands of miles of barbed-wire fencing that is in the vast majority not wildlife-friendly. Bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) and pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana) usually prefer to pass under these fences, and therefore the lower wire should be higher and smooth in order to decrease injury and facilitate passage. Yet mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and elk (Cervus canadensis) prefer to jump barbed-wire fences, and may get caught up in the wire strands with a leg, and die as if caught in a snare. Livestock fences hinder migrations and cause injury, mortality, and tremendous damage to wildlife.

Diseases originating in overcrowded domestic livestock kept in poor conditions can jump to wild native ungulate species, with unfortunate results. Livestock pathogens place bighorn sheep at risk of disease throughout the West, with authorized grazing on public lands a limiting factor for many populations. Disease bacteria from domestic sheep and goats grazing near bighorns have caused extensive pneumonia outbreaks, resulting in severe mortality and to the extermination of entire populations of native bighorns.

Outside of direct disease transmission, domestic livestock also impact wildlife through the wholesale degradation of vast areas of habitat.

The pygmy rabbit requires dense and tall sagebrush communities to thrive; cattle trample sagebrush cover and rabbit burrows, and compete for bunchgrass forage.

Spotted bats are vulnerable to habitat alteration, including loss or reduction in value of wet meadows and other foraging areas. Such impacts could result from overgrazing by livestock, water diversion, or changes in land use.

Greater sage-grouse used to number in the millions across the sagebrush-steppe, yet this bird is now greatly imperiled and crashing in populations. It deserves more protection under the Endangered Species Act. Sage-grouse require adequate vegetative cover to hide in, to avoid the many predators that hunt them in the wild such as ravens, coyotes, and hawks. Sage-grouse hens with their newly-hatched chicks seek the cover of native bunchgrasses and tall sagebrush, as well as tall meadow grass cover, as they seek food. They duck down and hide in the tall grass when approached by any suspicious onlooker--including humans. But cattle and domestic sheep grazing mows down this escape cover, reducing bunchgrasses and meadows to a mere stubble no better than a lawn or golf course. Sage-grouse cannot find shelter in these overgrazed habitats, and are predated by ravens, coyotes, and hawks at an unnaturally high level.

Sage-grouse are among the many native wildlife species at risk due to habitat degradation whose primary cause is grazing of public lands due to domestic livestock. To allow for recovery of sage-grouse and the many imperiled wildlife species of the west, livestock must be removed from western public lands.

Livestock’s Affect on Native Plant Species

A plant species is considered native if it was present before the arrival of humans. It either evolved locally or migrated on its own to its present locations without the assistance of people. In North America, plants are considered native if they were in place before the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th Century.

Native plants that evolved with other ecosystem constituents like wildlife, pollinators, and soil microorganisms form communities that are more resilient and resistant to perturbations like fire, drought, storms, insect outbreaks, and other stochastic events. This confers a degree of stability to the ecological landscape. Populations of individual species may fluctuate as environmental conditions ebb and flow, but, in general, the system is stable as long as the environmental factors that shaped the community remain within a normal range.

This resilience is especially valuable in the face of our rapidly changing climate. Diverse ecosystems are more likely to have the genetic variability needed to respond to extreme disturbances like climate change. For example, research is predicting that precipitation amounts will change in the future. Plants may be in for longer summer droughts. Those that can adapt to those conditions (by, for instance, altered germination patterns, longer dormancy periods, or physical changes to conserve water) may be able to survive in these new environments. The harsh conditions that are predicted will be challenging for many plant and animal species, but some will be favored by these new physical settings. Promoting healthy functioning native ecosystems and genetic diversity now means we will be better able to respond to the changes to come.

Unfortunately, land management agencies have a history of using introduced plants to revegetate degraded sites because their primary interest was to provide forage for non-native livestock, not restore native ecosystems. Now, however, their policy experts are starting to recognize the need to restore and maintain native plant communities, at least in theory.

This new direction is reflected in BLM policies and programs like the BLM Plant Conservation and Restoration Program and the Native Seed Strategy for Rehabilitation and Restoration. Unfortunately, these policies come with significant caveats that give staff on the ground discretion to avoid adhering to them and keep using non-native seeds in restoration projects. It’s true that native seed is often not available for restoration projects, and what is available is more expensive than non-native seed. Some non-native plants like crested wheatgrass also germinate and establish more reliably, an important consideration after treatments when the priority is to get vegetation growing on bare ground as soon as possible to reduce the risk of invasion by exotic species.

Perhaps the paramount interest, however, is that non-native forage species are a fast and reliable source of forage for livestock when ranchers pressure managers to allow livestock grazing on a site as soon as possible. Consequently, the agency’s direction to prioritize native species in seedings has loopholes that allow local offices to avoid using native seed if supplies are not available or if they are too expensive. Managers often split the difference by mixing native and non-native seeds. The result they are looking for is ostensibly a rapid establishment of non-natives followed by the eventual dominance of native plants and a more functional ecosystem over time. However, many non-native plants that have been developed for forage, once established, are not easily displaced. We have seen these seedings develop into monocultures of non-native plants that can’t provide the ecosystem stability that comes with more biodiverse vegetation. Efforts to remove these plants and restore native species have proved ineffective.

Agencies need to prioritize the development and expansion of native seed supplies to increase availability and bring the cost down. More importantly, they need to respond more urgently to the climate crisis by prioritizing re-establishment of native plant communities across the west rather than supporting a failing livestock industry at huge environmental and social cost. Our western landscapes, and ultimately our species, can’t afford anything less.

Livestock’s Contribution to Non-Native Plant Species

The BLM says that one of its highest priorities is to promote ecosystem health, and one of the greatest obstacles to achieving this goal is the rapid expansion of weeds across public lands. Indeed, the explosion of invasive exotic species into native ecosystems is one of the most impactful consequences of post-European contact land use practices.

Intact, functioning native vegetation communities often can resist the invasion of introduced plants--but some invasive species are spectacularly well-adapted for western environments and can under some conditions outcompete native plants. Cheatgrass is one of the examples most often cited, for good reason. It evolved in the sagebrush steppes of Asia, where it is a functioning component of the landscape. It may have had constraints in its native land that kept it in check, but those constraints are minimal in disturbed landscapes of North America. Cheatgrass arrived in North America in the late 1880s, perhaps in livestock feed, and it hasn’t looked back. Cheatgrass is currently estimated to cover roughly 100 million acres across the western US and is spreading rapidly.

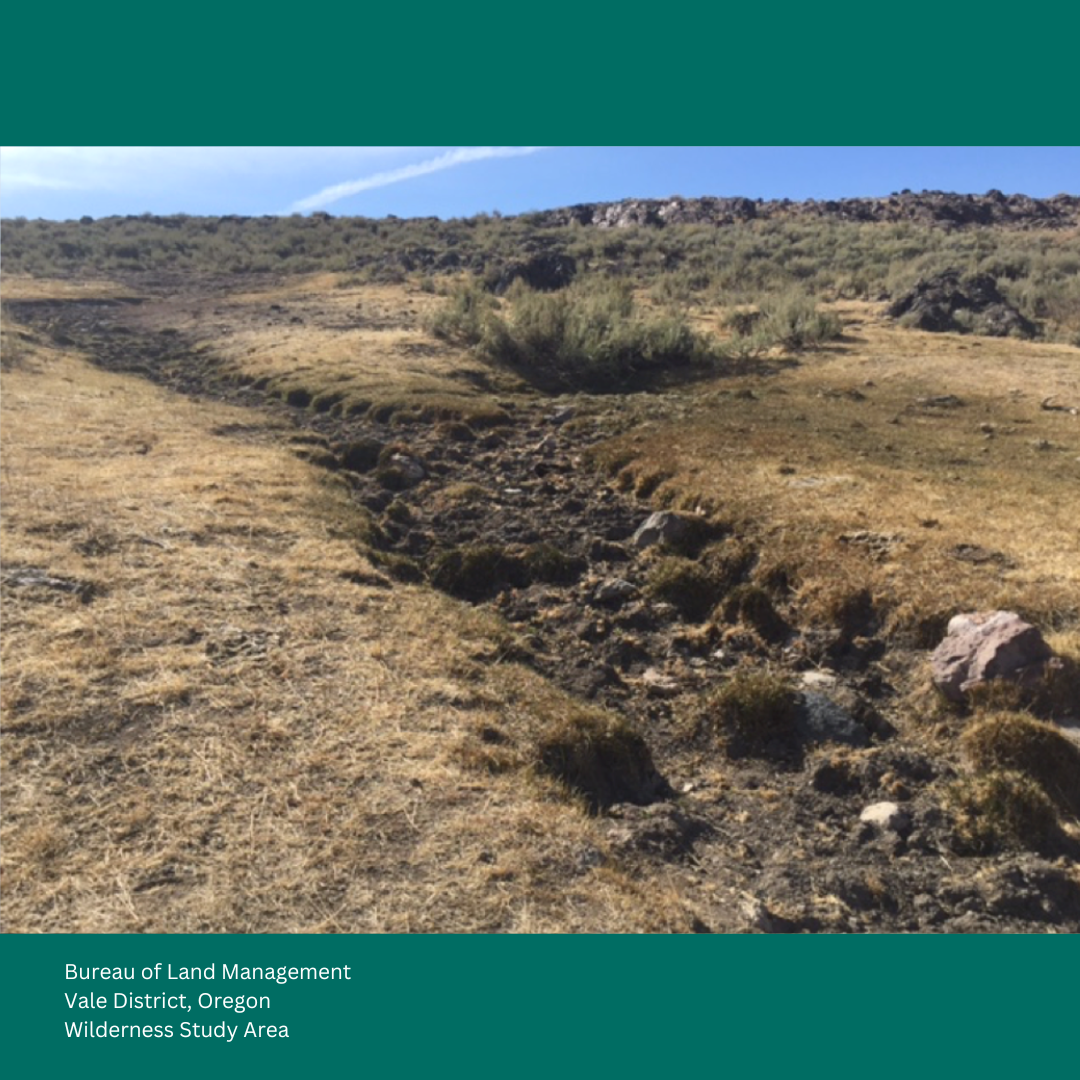

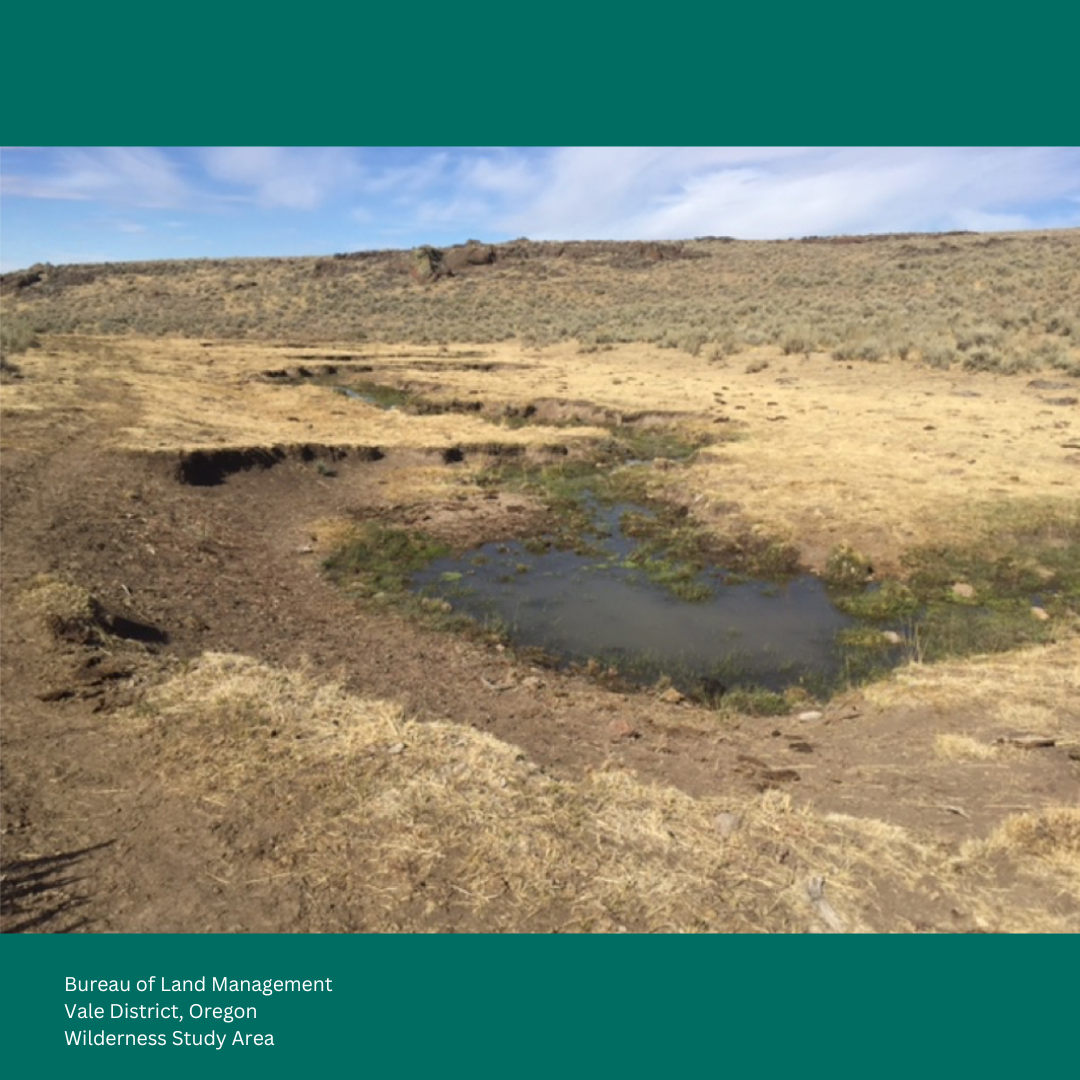

Cheatgrass, like many other species with an invasive habit, is an early successional annual plant that takes advantage of open, disturbed ground. It starts growing earlier in the year so it gets a jump on native species in the competition for water, space, and nutrients. It has some forage value when it first comes up, but after several weeks it dries out and becomes unpalatable. Cheatgrass and other invasives are best kept in check through protecting intact native ecosystems that have a diversity of established grasses, forbs, shrubs, trees, or biological soil crust appropriate for the site; minimal bare ground in these systems allows invasives less opportunity to take hold.

Natural disturbance creates some amount of bare soil in all ecosystems, but human activities have dramatically increased the bare ground available for exotics to invade. The ubiquity and intensity of livestock grazing makes this activity one of the most dramatic contributors to the explosion of annual invasive non-natives throughout the West. The more than 2 million non-native grazing animals on public lands every year create more bare ground through trampling and overuse of vegetation, while associated range projects necessary to support livestock operations in semiarid conditions (water troughs, pipeline, wells, fences, forage projects) also contribute to ground disturbance and non-native plant colonization. Land managers attempt to mitigate the contribution of livestock grazing to non-native invasion by requiring certified weed-free hay and cleaning of vehicles to prevent the introduction of weed seeds, but these stipulations are woefully inadequate. To reduce the habitat destruction caused by non-native invasion, land managers must stop creating conditions that facilitate their spread.